قائمة أقدم البنايات في العالم

هذه القائمة تشمل أقدم البنايات القائمة بذاتها والباقية حتى الآن. يعرف المبنى حسب هذا المقال بأنه أي بناية من صنع الإنسان واستعملت أو شغلت من قبله، ويجب أن يكون واضح المعالم مميز عن محيطه لا يقل ارتفاعه عن 1.5م.

حسب القارة

هذه القائمة تضم اقدم بناية لكل قارة من قارات العالم:

| المبنى | الصورة | البلد | القارة | تاريخ البناء | الاستخدام | ملاحظات |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| مهرغاره | باكستان | آسيا | 2600 ق.م | |||

| كوبيكلي تبه |  |

تركيا | أوروبا/آسيا | 9500 ق.م [1] | حرم | Oldest preserved momument that is located at eastern Turkey. The tell includes two phases of ritual use dating back to the 10th-8th millennium BCE. During the first phase (Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA)), circles of massive T-shaped stone pillars were erected.[2] |

| بارننز |  |

فرنسا | أوروبا | 4850 ق.م | Passage grave | تقع في شمال فنستير طوله 72م وعرضه 25م وارتفاعه أكثر من 8م.[3][4] |

| Sechin Bajo |  |

البيرو | أمريكا الجنوبية | 3500 ق.م | Plaza | The oldest known building in the Americas.[5][6] |

| هرم زوسر |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | 2667 - 2648 ق.م | Burial | البناء الاقدم المكون من احجار كبيرة الحجم.[7] |

| شهر سوخته |  |

إيران | آسيا | 3200 ق.م | The remains of the mud brick city[8] | |

| هرم كويكولكو الدائري |  |

المكسيك | أمريكا الشمالية | 800 - 600 ق.م | Ceremonial center | One of the oldest standing structures of the Mesoamerican cultures.[9] |

| ويبي هايس ستون فورت |  |

أستراليا | أسترالاسيا | 1629 ق.م | Defensive fort | Oldest known building in Australia, a defensive fort used by the survivors of the باتافيا shipwreck on West Wallabi Island.[10] |

| كوخ كيب ادار |  |

منطقة روس | القارة القطبية الجنوبية | 1899 ق.م | Explorers' huts | مبنى خشبي بني من قبل كارستن بورشغرفنك في أرض فكتوريا.[11] |

حسب العمر

هذه القائمة تضم اقدم البنايات حول العالم بالترتيب من الاقدم إلى الأحدث: The following are amongst the oldest buildings in the world. Many of them are brick structures. There are numerous extant structures that survive in the جزر أوركني islands of Scotland, some of the best known of which are part of the قلب أوركني النيوليتي موقع تراث عالمي.[12] The list also contains many large buildings from the Egyptian المملكة المصرية القديمة.

| المبنى | الصورة | البلد | القارة | تاريخ البناء | الاستخدام | ملاحظات |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| كوبيكلي تبه |  |

تركيا | آسيا | c. 9500 ق.م | حرم | Oldest preserved momument located in eastern Turkey. The tell includes two phases of ritual use dating back to the 10th-8th millennium ق.مE. During the first phase (Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA)), circles of massive T-shaped stone pillars were erected.[2] |

| بارنينيز |  |

فرنسا | أوروبا | 4850 ق.م | Passage grave | Located in northern فنستير (إقليم فرنسي) and partially restored. According to André Malraux it would have been better named ‘The Prehistoric Parthenon’. The structure is 72 m long, 25 m wide and over 8 m high.[3][4] |

| تومولوس من بوغون | فرنسا | أوروبا | 4700 ق.م | جثوة | A complex of tombs with varying dates near بواتييه, the oldest being F0.[3] | |

| تومولوس سانت ميشيل | .jpg.webp) |

فرنسا | أوروبا | 4500 ق.م | جثوة | The tumulus forms what is almost an artificial أكمة أوراسية of more than 30,000m3 (125m long, 60m wide and 10m high).[13][14] |

| جبل اكودي |  |

إيطاليا | أوروبا | 4000–3650 ق.م [15][16] | Possibly an open-air temple, ziggurat, or a step pyramid, mastaba. | A trapezoidal platform on an artificial mound, reached by a sloped causeway. New radiocarbon dating (2011) allow us to date the building of the first monument to 4000–3650 ق.م, the second shrine dating to 3500–3000 ق.م."[17] |

| زر من هور |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 3700 ق.م | House | Oldest preserved stone house in north west Europe.[18][19][20] |

| غانتيجا | .jpg.webp) |

مالطا | أوروبا | 3700 ق.م | معبد | Two structures on the island of غودش. The second was built four centuries after the oldest.[21][22] |

| رابية كنت الغربية الطويلة |  |

إنجلترا | أوروبا | 3650 ق.م | قبر | Located near Silbury Hill and أفيبري stone circle.[23] |

| ليستوجيل |  |

جزيرة أيرلندا | أوروبا | 3550 ق.م | Passage Tomb | At the centre of the Carrowmore passage tomb cluster, a simple box-shaped chamber is surrounded by a kerb c.34m in diameter and partly covered by a cairn. It has been partly reconstructed.[24] |

| سيتشين باجو |  |

بيرو | أمريكا الجنوبية | 3500 ق.م | Plaza | The oldest known building in the Americas.[6] |

| لا هوج بيي |  |

جيرزي | أوروبا | 3500 ق.م | Passage grave | An 18.6 metre long passage chamber. The chapel above is medieval.[25] |

| ميدهو تشامبرد كايرن |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 3500 ق.م | قبر | A well-preserved example of the جزر أوركني-Cromarty type on the island of Rousay.[26] |

| مقبرة مرور غافرينيس |  |

فرنسا | أوروبا | 3500 ق.م | قبر | On a small island, situated in the Gulf of Morbihan.[27] |

| وايلاند سميثي |  |

إنجلترا | أوروبا | 3460 ق.م | Chamber tomb | A barrow constructed on top of an older burial chamber.[28] |

| أونستان تشامبرد كايرن |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 3450 ق.م | قبر | Excavated in 1884, when grave goods were found, giving their name to Unstan ware.[29][30][31] |

| قاعة كنو أوف يارسو |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 3350 ق.م | قبر | One of several Rousay tombs. It contained numerous deer skeletons when excavated in the 1930s.[29][32][33] |

| قاعة كوانترنيس |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 3250 ق.م | قبر | The remains of 157 individuals were found inside when excavated in the 1970s.[29][34] |

| هياكل تاركين |  |

مالطا | أوروبا | 3250 ق.م | معبد | Part of the Megalithic Temples of Malta World Heritage Site.[21][35] |

| شهر سوخته |  |

إيران | آسيا | 3200BC | Settlement | a rich source of information regarding the emergence of complex societies and contacts between them in the third millennium [36] |

| سكارا براي |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 3180 ق.م | Settlement | Northern Europe's best preserved Neolithic village.[37] |

| قبر النسور |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 3150 ق.م | قبر | In use for 800 years or more. Numerous bird bones were found here, predominantly عقاب أبيض الذنب.[38][39] |

| نيوغرانغ |  |

جزيرة أيرلندا | أوروبا | 3100–2900 ق.م | Burial | Partially reconstructed around original passage grave.[40] |

| دولمن دي باجنوه |  |

فرنسا | أوروبا | 3000 ق.م | Dolmen | This is the largest dolmen in France, and perhaps the world, the overall length of the dolmen is 23 m (75 ft), with the internal chamber at over 18 m (60 ft) in length and at least 3m high.[41][42][43] |

| جراي كيرنز من كامستر |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 3000 ق.م or older | قبر | Located near Upper Camster in كيثنس.[44][45] |

| هيلبرجاتستيو |  |

الدنمارك | أوروبا | 3000 ق.م | Passage grave | The grave is concealed by a round barrow on the southern tip of the island of Langeland. One of the skulls found there showed traces of the world's earliest dentistry work.[46][47][48] |

| مايكوب كورغانز |  |

روسيا | أوروبا | 3000 ق.م | قبر | There are numerous tombs, some perhaps originating in the حضارة مايكوب, in the North Caucasus.[49][50] |

| قاعة تافيرسو تويك |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 3000 ق.م | قبر | Unusually, there is an upper and lower chamber.[51] |

| قاعة هولم بابا |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 3000 ق.م | قبر | The central chamber is over 20 metres long.[52][53] |

| باربا لانغاس |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 3000 ق.م | قبر | The best preserved chambered cairn in the هبرديس.[54][55] |

| قاعة كوين هيل |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 3000 ق.م | قبر | Excavated in 1901, when it was found to contain the bones of men, dogs and oxen.[56][57] |

| قاعة كوينيس |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 2900 ق.م | قبر | An arc of Bronze Age mounds surrounds this cairn on the island of Sanday.[58] |

| مايشو |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 2800 ق.م | قبر | The entrance passage is 36 قدم (11 م) long and leads to the central chamber measuring about 15 قدم (4.6 م) on each side.[59][60] |

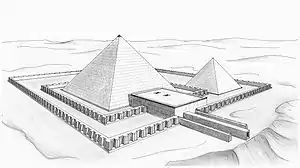

| هرم زوسر |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | 2667–2648 ق.م | Burial | Earliest large-scale cut stone construction.[61] |

| موهينجو دارو | باكستان | آسيا | 2600BC;BC | brick storage structures | - | |

| دولافيرا |  |

الهند | آسيا | 2650 ق.م-2100 ق.م | Brick water reservoirs, with steps, circular graves & ruins of well planned town | A complex of ruins with varying dates at Dholavira.[63][64][65] |

| كارال | بيرو | أمريكا الجنوبية | 2600 ق.م | Pyramid | Once thought to be the oldest building in South America.[66] | |

| ميدوم |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2580 ق.م | قبر | أسرة مصرية رابعة structure completed by سنفرو. |

| هرم سنفرو |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2580 ق.م | قبر | A second structure completed by Sneferu. |

| الهرم الأحمر | .jpg.webp) |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2580 ق.م | قبر | Third large pyramid completed by Sneferu.[67] |

| الهرم الأكبر |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | 2560 ق.م | قبر | Mausoleum for أسرة مصرية رابعة Egyptian Pharaoh خوفو.[68] |

| نوث |  |

جزيرة أيرلندا | أوروبا | Between 2500-2000 ق.م | Passage grave | [69] |

| هرم خفرع |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2500 ق.م | قبر | One of the أهرام الجيزة.[70] |

| هرم منقرع |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2500 ق.م | قبر | منقرع was probably خفرع's successor. |

| دوث |  |

جزيرة أيرلندا | أوروبا | 2500 ق.م | قبر | The cairn is about 85 متر (280 قدم) in diameter and 15 متر (50 قدم) high.[69] |

| هرم أوسركاف |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2480 ق.م | قبر | Located close to Pyramid of Djoser.[71] |

| هرم ساحورع |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2480 ق.م | قبر | Built for ساحورع.[72] |

| هرم نيفيرركار كاكاي |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2460 ق.م | قبر | Built for نفر إر كارع كاكاي.[72] |

| هرم نيفريفري |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2455 ق.م | قبر | Never completed but does contain a tomb.[72] |

| هرم ني أوسر رع |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2425 ق.م | قبر | [73] |

| هرم دجيدكار-إيسيسي |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2370 ق.م | قبر | |

| هرم أوناس |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2340 ق.م | قبر | [74] |

| هرم تتي |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2330 ق.م | قبر | |

| قبر وتد لاباكالي |  |

جزيرة أيرلندا | أوروبا | c. 2300 ق.م | قبر | The largest wedge tomb in Ireland.[بحاجة لمصدر] |

| هرم ميرينري |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2275 ق.م | قبر | Built for مرن رع الأول but not completed. |

| هرم بيبي الثاني نفر كا رع |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 2180 ق.م | قبر | |

| حجارة كرانتيت | اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 2130 ق.م | قبر | Discovered in 1998 near كيركوول.[75][76] | |

| دولمن دي فييرا |  |

إسبانيا | أوروبا | 2000 ق.م | قبر | The Dolmen de Viera or Dolmen de los Hermanos Viera is a dolmen—a type of single-chamber megalithic tomb[77] |

| قبر روبها أن دنين |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 2000 ق.م or older | قبر | [78][79][80] |

| قاعة كوريموني |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 2000 ق.م or older | قبر | A Clava-type passage grave surrounded by a circle of 11 standing stones.[81][82] |

| كنوسوس |  |

اليونان | أوروبا | 2000–1300 ق.م | Palace | حضارة مينوسية structure on a Neolithic site.[83] |

| برين كللي ددو (للنددنيل فاب) |  |

ويلز | أوروبا | 2000 ق.م | قبر | Located on the island of أنغلزي.[84] |

| بالنواران من كلافا |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 2000 ق.م | قبر | The largest of three is the north-east cairn, which was partially reconstructed in the 19th century. The central cairn may have been used as a funeral pyre.[80][85][86] |

| فينكوي كايرن إيداي |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 2000 ق.م | قبر | [87] |

| هرم أمنمحات الأول |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 1960 ق.م | قبر | |

| هرم سنوسرت الأول |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 1920 ق.م | قبر | |

| هرم سنوسرت الثاني |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 1875 ق.م | قبر | |

| هرم سنوسرت الثالث |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 1835 ق.م | قبر | Built for سنوسرت الثالث |

| الهرم الأسود |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 1820 ق.م | قبر | Built for أمنمحات الثالث, it has multiple structural deficits. |

| هوارة المقطع |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 1810 ق.م | قبر | Also built for Amenemhat III. |

| هرم خندجر |  |

مصر | أفريقيا | c. 1760 ق.م | قبر | Built for pharaoh خنجر اوسركاف |

| نوراغي سانتو أنتين |  |

إيطاليا | أوروبا | 1600 ق.م | Possibly a fort | The second tallest of these megalithic edifices found in سردينيا and tallest still standing.[88] |

| سو نوراكسي دي باروميني |  |

إيطاليا | أوروبا | 1500 ق.م | Possibly a fort or a palace | The palace of Barumini is formed by a huge quatrefoiled نوراك, whose central tower is its oldest construction. Originally it was almost 20 metres high and divided into three floors.[89][90] |

| نوراغي لا بريسجيونا |  |

إيطاليا | أوروبا | 1400 ق.م | Possibly a fort | The monument has a central tower and 2 side towers, the former with an entrance defined by a massive lintel of 3.20 m. The central chamber has a false dome, which is more than 6 meters high.[91] |

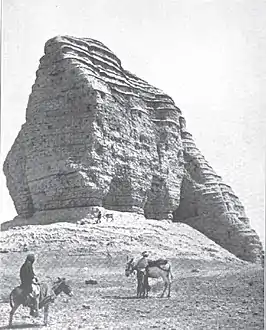

| زغورات زقورة عقرقوف |  |

العراق | آسيا | 14th century ق.م | Probably religious rituals | Built for the كيشيون King كوريغالزو الأول.[92] |

| خزينة أتريوس |  |

اليونان | أوروبا | 1250 ق.م | قبر | The tallest and widest dome in the world for over a thousand years.[93] |

| جغا زنبيل |  |

إيران | آسيا | 1250 ق.م | معبد | One of the few extant زقورةs outside of بلاد الرافدين.[94] |

| نافيتا دي إس تودونز |  |

إسبانيا | أوروبا | 1200-750 ق.م | Ossuary | The most famous جندل (آثار) chamber tomb in منورقة. |

| دون أونغاسا |  |

جزيرة أيرلندا | أوروبا | 1100 ق.م | Fort | Dún Aonghasa, also called Dun Aengus, has been described as one of the most spectacular prehistoric monuments in western Europe. The drystone walled hillfort is made up of 4 widely spaced concentric ramparts.[96][97] |

| قبر الملك |  |

السويد | أوروبا | 1000 ق.م | قبر | Near Kivik is the remains of an unusually grand عصر برونزي شمالي double burial.[98] |

| هرم كويكويلكو الدائري |  |

المكسيك | أمريكا الشمالية | 800–600 ق.م | Ceremonial center | One of the oldest standing structures of the Mesoamerican cultures. First steps in the creation of a sun based calendar.[9] |

| حصن فان |  |

تركيا | آسيا | 750 ق.م | Fortress | Massive أورارتو stone fortification overlooking تشبه. |

| متحف مدينة تشرفيتيري وتاركوينيا |  |

إيطاليا | أوروبا | 700 ق.م | قبرs | These الحضارة الإتروسكانية necropolises contain thousands of tombs, some organized in a city-like plan.[99] |

| معبد هيرا، بيستوم |  |

إيطاليا | أوروبا | 550 ق.م | معبد | Part of a complex of three great temples in Doric style.[100] |

| قبر سايروس |  |

إيران | آسيا | 530 ق.م | قبر | قبر of كورش الكبير, located in باسارغاد |

| بارثينون |  |

اليونان | أوروبا | 432–447 ق.م | معبد | In the أكروبوليس أثينا |

| ضريح كازانلاك التراقي |  |

بلغاريا | أوروبا | 300–400 ق.م | قبر | Located near Seutopolis, the capital city of the تراقيون king Seuthes III, and part of a large necropolis.[101] |

| Sanchi Stupa |  |

الهند | آسيا | 300 ق.م | Buddhist temple | In the village of Sanchi |

| دامك ستوبا |  |

الهند | آسيا | 249 ق.م | Buddhist Temple | In Sarnath, فاراناسي |

| بروش موسى |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 100 ق.م | Broch | Located in جزر شتلاند it is among the best-preserved عصر ما قبل التاريخ buildings in Europe.[102][103] |

| دان كارلاي |  |

اسكتلندا | أوروبا | 100 ق.م | Broch | Built in the first century ق.مE [104] |

| متحف لي تشنغ أوك هان تومب |  |

هونغ كونغ | آسيا | 25 AD | قبر | |

| كولوسيوم |  |

إيطاليا | أوروبا | 70–80 AD | Amphitheatre |

المراجع

- Stone Pages Archaeo News: Which came first, monumental building projects or farming? نسخة محفوظة 01 أغسطس 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Curry, Andrew (نوفمبر 2008). "Gobekli Tepe: The World's First Temple?". Smithsonian.com. مؤرشف من الأصل في 01 يناير 2014. اطلع عليه بتاريخ August 2, 2013. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة); Cite journal requires|journal=(مساعدة) - Chris Scarre, Roy Switsur, Jean-Pierre Mohen (1993) "New radiocarbon dates from Bougon and the chronology of French passage-graves". Antiquity/The Free Library. Retrieved 11 September 2013. نسخة محفوظة 05 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين. [وصلة مكسورة]

- Gibson, Marion; Trower, Shelley; Tregidga, Garry (2013) Mysticism, Myth and Celtic Identity. Routledge. Abingdon. p. 133 نسخة محفوظة 18 يوليو 2014 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Senchin Bajo – Plaza in Peru may be the America's oldest urban site". Gogeometry.com. Retrieved 12 July 2012 نسخة محفوظة 22 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- McDonnell, Patrick J. (February 26, 2008) "A new find is the Americas' oldest known urban site". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 12 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 19 يناير 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Shaw, Ian, ed (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 480

- Shahr-I Sokhta|url=http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1456/ نسخة محفوظة 2020-08-30 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Zona Arqueológica Cuicuilco". Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. (Spanish). Retrieved 12 July 2012 نسخة محفوظة 03 مايو 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Elder, Bruce (2005). "The Brutal Shore". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 11 September 2011. نسخة محفوظة 05 يناير 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Historic Huts in the Antarctic from the 'Heroic Age'." Antarctic-Circle.org. Retrieved 8 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 27 مايو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Heart of Neolithic Orkney". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 29 ديسمبر 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "The Saint-Michel Tumulus". Culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 11 September 2013. نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Saint-Michel tumulus". Megalithic Portal. Retrieved 11 September 2013. نسخة محفوظة 12 أبريل 2018 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20160304001503/http://arheologija.ff.uni-lj.si/documenta/pdf38/38_16.pdf. مؤرشف من الأصل (PDF) في 4 مارس 2016. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة); مفقود أو فارغ|title=(مساعدة) - Delfino,Carlo (ed) (2000) "The Prehistoric Altar of Monte d'Accoddi". (pdf) Archaeological Sardinia. 29. Retrieved 14 October 2013. p. 45. [وصلة مكسورة] نسخة محفوظة 03 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Blake, Emma; Arthur Bernard Knapp (2004). The archaeology of Mediterranean prehistory. Wiley Blackwell. صفحة 117. ISBN 978-0-631-23268-1. مؤرشف من الأصل في 25 يناير 2020. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 31 أغسطس 2011. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - "Knap of Howar" اسكتلندا التاريخية [الإنجليزية]. Retrieved 23 Sept 2011. نسخة محفوظة 03 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "The Knap o' Howar, Papay". Orkneyjar. Retrieved 13 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 15 يوليو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Wickham-Jones, Caroline (2007) Orkney: A Historical Guide. Edinburgh. Birlinn. p. 40.

- "Megalithic Temples of Malta". UNESCO. Retrieved 15 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 17 يوليو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Mcintosh, Jane (2009) Handbook of Life in Prehistoric Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 261-62Retrieved 12 August 2012. نسخة محفوظة 29 مايو 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "West Kennet Long Barrow, Avebury" التراث الإنكليزي. Retrieved 15 July 2012. "نسخة مؤرشفة". Archived from the original on 7 أغسطس 2012. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 19 يوليو 2015. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)صيانة CS1: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) - Alastair Whittle, Frances Healy & Alex Bayliss. Gathering time: dating the Early Neolithic enclosures of southern Britain and Ireland. 2 volumes. 2011. Oxford: Oxbow; 978-1-84217-425-8

- "La Hougue Bie". Wondermondo. مؤرشف من الأصل في 15 يونيو 2018. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 12 يوليو 2012. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - "The Midhowe Stalled Cairn, Rousay". Orkneyjar. Retrieved 13 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 15 أبريل 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Milisauskas, Sarunas (2002) European Prehistory: A Survey. Birkhäuser p. 231

- "Wayland's Smithy". English Heritage. Retrieved 10 September 2013. نسخة محفوظة 07 أغسطس 2012 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Fraser, David (1980) Investigations in Neolithic Orkney. Glasgow Archaeological Journal. 7 p. 13. ISSN 1471-5767

- "Unstan Chambered Cairn". Historic Scotland. Retrieved 21 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 24 سبتمبر 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Wickham-Jones, Caroline (2007) Orkney: A Historical Guide. Edinburgh. Birlinn. p. 48

- "Rousay, Knowe of Yarso". Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 12 مارس 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Wickham-Jones, Caroline (2007) Orkney: A Historical Guide. Edinburgh. Birlinn. pp. 56-57

- Wickham-Jones, Caroline (2007) Orkney: A Historical Guide. Edinburgh. Birlinn. p. 50

- Cilia, Daniel (2004-04-08). "Tarxien". The Megalithic temples of Malta. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 07 يوليو 2007. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Shahr-i Sokhta - UNESCO World Heritage Centre نسخة محفوظة 19 يوليو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Clarke, David (2000) Skara Brae; World Heritage Site. اسكتلندا التاريخية [الإنجليزية]. ISBN 1900168979

- "Tomb of the Eagles" tomboftheeagles.co.uk. Retrieved 11 February 2008. نسخة محفوظة 20 يوليو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Hedges, J. 1990. Tomb of the Eagles: Death and Life in a Stone Age Tribe. New Amsterdam Books. ISBN 0-941533-05-0 p. 73

- O’Kelly, Michael J. 1982. Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend. London: Thames and Hudson. Page 13.

- The Loire Dolmens, France نسخة محفوظة 01 مايو 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Le Grand Dolmen de Bagneux" en. مؤرشف من الأصل في 12 أبريل 2018. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 17 ديسمبر 2019. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة); Invalid|script-title=: missing prefix (مساعدة) - Le Grand Dolmen de Bagneux (Burial Chamber) | France | The Modern Antiquarian.com نسخة محفوظة 08 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Grey Cairns of Camster". Megalithic Portal. Retrieved 21 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 04 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Grey Cairns of Camster". Historic Scotland. Retrieved 21 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 03 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Danish National Museum. Retrieved 12 July 2012نسخة محفوظة 28 سبتمبر 2011 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Gron, Ole "The World's Oldest Root-canal Work". Kulturarv.dk. Retrieved 12 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 12 يوليو 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Hulbjerg Jættestue". The Megalithic Portal. Retrieved 12 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 04 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Лаборатория альтернативной истории نسخة محفوظة 03 يوليو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Markovin, V.I. "western Caucasian Dolmens". (pdf) Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia. 41, no. 4 (Spring 2002), pp. 68–88 نسخة محفوظة 07 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "The Taversoe Tuick, Rousay" Orkneyjar. Retrieved17 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 8 مارس 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين. [وصلة مكسورة]

- "Info Board, Holm of Papa Westray Cairn" Wikimedia Commons/Historic Scotland. Retrieved17 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 16 مايو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Wickham-Jones, Caroline (2007) Orkney: A Historical Guide. Edinburgh. Birlinn pp. 62-63

- "North Uist, Barpa Langass". Canmore. Retrieved 18 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 13 فبراير 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Armit, Ian (1996) The archaeology of Skye and the Western Isles. Edinburgh University Press/Historic Scotland. p. 71

- "The Cuween Hill Cairn, Firth". Orkneyjar. Retrieved 21 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 14 أبريل 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Cuween Hill Chambered Cairn". Historic Scotland. Retrieved 21 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 04 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "The Quoyness Cairn, Sanday". Orkneyjar. Retrieved 19 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 15 أبريل 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Childe, V. Gordon; W. Douglas Simpson (1952). Illustrated History of Ancient Monuments: Vol. VI Scotland. Edinburgh: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) pp.18-19 - Ritchie, Graham & Anna (1981). Scotland: Archaeology and Early History. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27365-0. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) p. 29 - Shaw, Ian, ed (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 480. (ردمك 0-19-815034-2).

- موهينجو دارو.

- Subramanian, T S (5–18 June 2010). "The rise and fall of a Harappan City". Frontline. 27 (12). مؤرشف من الأصل في 25 يناير 2020. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 04 يوليو 2012. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark. Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Oxford University Press. 1998

- "Will Dholavira ruins rewrite history of ancient theatre? by Robin David". Times of India. 1 February 2011. مؤرشف من الأصل في 8 مارس 2020. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 16 يناير 2013. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - "Oldest evidence of city life in the Americas reported in Science, early urban planners emerge as power players". American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 12 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 13 ديسمبر 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "King Snefru: The First Great Pyramid Builder". Fathom. Retrieved 17 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 21 مايو 2012 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Egyptian researchers claim to have exact date for Great Pyramid". Ria Novosti. Retrieved 17 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 05 أغسطس 2011 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Harbison, Peter. (1970). Guide to the National Monuments of Ireland. Gill & Macmillan. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - "Pyramid of Chefren". SkyscraperPage. Retrieved 17 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 03 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Winston, Alan "The Pyramid Complex of Userkaf at Saqqara". Retrieved 18 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 14 يوليو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Shaw, Ian, المحرر (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. صفحة 480. ISBN 0-19-815034-2. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Lehner, Mark (1997) The Complete Pyramids London: Thames and Hudson pp. 148-49 ISBN 0-500-05084-8

- Jaromir Malek, "The Old Kingdom (c.2160-2055 ق.مE)" in Ian Shaw (editor) (2000) The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: University Press. p. 112

- "C14 Radiocarbon dating for Crantit" Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 8 مارس 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين. [وصلة مكسورة]

- "Crantit" Canmore. Retrieved 20 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 12 مايو 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Dólmenes de Antequera نسخة محفوظة 31 يوليو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Armit, Ian (1996) The archaeology of Skye and the Western Isles. Edinburgh University Press/Historic Scotland. p. 73

- "Skye, Rubh' An Dunain, 'Viking Canal' ". Canmore. Retrieved 7 May 2011. نسخة محفوظة 22 أكتوبر 2012 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "The Cairns of Clava, Scottish Highlands". The Heritage Trail. Retrieved 19 July 2012. [وصلة مكسورة] نسخة محفوظة 03 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Corrimony Chambered Cairn & RSPB Nature Reserve". Glen Affric.org. Retrieved 21 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 07 أكتوبر 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Corrimony Chambered Cairn". Historic Scotland. Retrieved 21 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 04 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Knossos". Interkriti. Retrieved 12 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 17 يوليو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Bryn Celli Ddu". Ancient Britain Retrieved 18 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 18 أكتوبر 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "A Visitors’ Guide to Balnuaran of Clava: A prehistoric cemetery. (2012) Historic Scotland.

- Bradley, Richard (1996) Excavation at Balnuaran of Clava, 1994 and 1995. Highland Council.

- Uney, Graham (2010) Walking on the Orkney and Shetland Isles: 80 Walks in the Northern Isles. Cicerone Press. p. 71

- "Nuraghe Santu Antine e Museo della Valle dei Nuraghi". Museo Valle de Inuraghi. Retrieved 12 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 18 نوفمبر 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Su Nuraxi di Barumini". Google World Wonders. Retrieved 8 August 2012. نسخة محفوظة 30 يوليو 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Su Nuraxi di Barumini". UNESCO. Retrieved 8 August 2012. نسخة محفوظة 17 يوليو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Nuraghe la Prisgiona -Arzachena Costa Smeralda". Beepworld. Retrieved 8 August 2012. نسخة محفوظة 05 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- J A Brinkman, Materials and Studies for Kassite History Vol I: A Catalogue of Cuneiform Sources Pertaining to Specific Monarchs of the Kassite Dynasty, Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 1976, ISBN 0-918986-00-1

- "Treasury of Atreus" Structurae.de. Retrieved 12 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 20 أكتوبر 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Chogha Zanbil" The Megalithic Portal. Retrieved 13 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 04 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Dun Aonghasa". Archaeology Travel. Retrieved 8 August 2012. نسخة محفوظة 8 مارس 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين. [وصلة مكسورة]

- "Dún Aonghasa". The Discovery Programme. Retrieved 8 August 2012 نسخة محفوظة 10 أبريل 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين. [وصلة مكسورة]

- Goldhahn, Joakim (2005) Bredarör i Kivik. Department of Archaeology, University of Gothenburg. Retrieved 12 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 02 مارس 2012 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Necropolises of Cerveteri and Tarquinia". UNESCO. Retrieved 20 August 2012. نسخة محفوظة 08 يوليو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Cilento and Vallo di Diano National Park with the Archeological sites of Paestum and Velia, and the Certosa di Padula". UNESCO. Retrieved 12 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 03 مايو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- "Thracian Tomb of Kazanlak". UNESCO. Retrieved 12 July 2012. نسخة محفوظة 04 يوليو 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Fojut, Noel (1981)"Is Mousa a broch?" Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot. 111 pp. 220-228. نسخة محفوظة 11 يونيو 2007 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Armit, I. (2003) Towers in the North: The Brochs of Scotland. Stroud. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1932-3 p. 15.

- "Doune Broch" en. مؤرشف من الأصل في 14 يناير 2013. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 30 ديسمبر 2019. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة); Invalid|script-title=: missing prefix (مساعدة)

- بوابة عمارة

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.