سكان المجر

هذه مقالة عن ملامح الديموغرافيا لسكان المجر، بما في ذلك الكثافة السكانية، والعرق، ومستوى التعليم، والصحة، والوضع الاقتصادي، والانتماءات الدينية وجوانب أخرى.

السكان

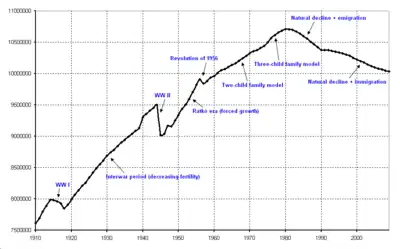

التركيبة السكانية في الاساس من المجر (895) يعتمد على حجم السكان والهنغارية وصول وحجم السلافية (ويبقى من أفار-السلافية) عدد السكان في ذلك الوقت. يذكر مصدر واحد 200 000 و 400 السلاف الهنغاريين، 000 [1] في حين مصادر أخرى في كثير من الأحيان لا تعطي تقديرات لكليهما، مما يجعل المقارنة أكثر صعوبة. وتشير التقديرات في كثير من الأحيان حجم السكان الهنغارية حول 895 بين 120 000 و 000 600، [2] مع عدد من التقديرات في نطاق 000 400-600. [1] [3] [4] مصادر أخرى تذكر فقط قوة قتالية من المحاربين المجرية 25 000 التي استخدمت في الهجوم، [5] [6] في حين امتنع عن تقدير عدد السكان بمن فيهم النساء والأطفال والمحاربين عدم المشاركة في الغزو. في التركيبة السكانية التاريخية أكبر صدمة في وقت سابق وكان الغزو المغولي من المجر، واصاب عدة كما أخذت تؤثر سلبا على سكان البلاد. وفقا لعلماء الديموغرافيا، وقدم حوالي 80 في المئة من السكان من المجريين قبل معركة موهاج، أمست مجموعة الهنغارية العرقية أقلية في بلده بعد الحرب Rákóczi من أجل الاستقلال. تغييرات الإقليمية الكبرى المجر متجانسة عرقيا بعد الحرب العالمية الأولى في الوقت الحاضر، أكثر من تسعة أعشار السكان الهنغارية عرقيا ويتحدث المجري للغة الأم. [7]

900-1910

| Time | Population | Percentage rate of مجريون (without Kingdom of Croatia) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| حوالي 900 بعد الميلاد | حوالي 600,000[1] | 66%[1][2] | |

| 1000 | 1,000,000-1,500,000[3] | ||

| 1222 | 2,000,000[4] | 70–80%[5][6] | The time of the Golden Bull. The last estimate before the الغزو المغولي لأوروبا. |

| 1242 | 1,200,000[6] | Population decreased after the الغزو المغولي لأوروبا(estimations about population loss are between 20% and 50%).[7] | |

| 1300 | 2,000,000[8] | ||

| 1348 | Before the plague (at the time of the آل أنجو الكابيتيون kings.) | ||

| 1370 | حوالي 2,000,000 | 60–70%[6] | |

| 1400 | |||

| 1490 | Before the Ottoman conquest (about 3.2 million Hungarians). | ||

| 1600 | Populations of Royal Hungary, Transylvania and Ottoman Hungary together. | ||

| 1699 | At the time of معاهدة كارلوفجة (not more than 2 million Hungarians). | ||

| 1711 | At the end of Kuruc War, starting date of the organized resettlement. | ||

| 1720 | |||

| 1790 | End of the organized resettlement, approximately 800 new German villages were established between 1711 and 1780.[46] | ||

| 1828 | 11,495,536 | 40-45%[بحاجة لمصدر] | |

| 1837 | |||

| 1846 | 12,033,399 | Two years before الثورة المجرية 1848. | |

| 1850 | 11,600,000 |

|

|

| 1880 | 13,749,603 | 46% | |

| 1900 | 16,838,255 | 51.4%[50] | |

| 1910 | 18,264,533 | 5% Jews (counted according to their mother tongue). |

ملاحظة: تشير البيانات إلى أراضي المملكة من المجر، وليس في الوقت الحاضر المجر.

منذ عام 1900

الإحصاءات التالية الديموغرافية هي من CIA Factbook اعتبارا من شهر سبتمبر عام 2009، ما لم يتبين خلاف ذلك.

هيكل العمر:

0–14 years: 15% (male 763,553/female 720,112)

15–64 years: 69.3% (male 3,384,961/female 3,475,135)

65 years and over: 15.8% (male 566,067/female 995,768) (2009 est.)

نسبة الجنس:

at birth:

1.06 male(s)/female

under 15 years:

1.06 male(s)/female

15–64 years:

0.97 male(s)/female

65 years and over:

0.57 male(s)/female

total population:

0.91 male(s)/female (2009 est.)

المجموعات العرقية واللغوية

المراجع

- A Country Study: Hungary. Federal Research Division, مكتبة الكونغرس. مؤرشف من الأصل في 13 يونيو 2019. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 06 مارس 2009. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Edgar C. Polomé, Essays on Germanic religion, Institute for the Study of Man, 1989, p. 150 نسخة محفوظة 18 يناير 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Marcell Sebők, The man of many devices, who wandered full many ways--: festschrift in honour of János M. Bak, Central European University Press, 1999, p. 658 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Nóra Berend, At the gate of Christendom: Jews, Muslims, and "pagans" in medieval Hungary, c. 1000-c. 1300, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 63-72 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Hungary. (2009). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 11, 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/276730/Hungary نسخة محفوظة 25 سبتمبر 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Historical World Atlas. With the commendation of the الجمعية الجغرافية الملكية. Carthographia, بودابست, المجر, 2005. ISBN 963-352-002-9CM

- Peter Purton, A History of the Late Medieval Siege, 1200-1500, Boydell & Brewer, 2009, p. 15 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Tore Nyberg, Lars Bisgaard, Medieval spirituality in Scandinavia and Europe: a collection of essays in honour of Tore Nyberg, Odense University Press, 2001, p. 170 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Josiah Cox Russell, Late ancient and medieval population, American Philosophical Society, 1958, p. 100 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- György Enyedi, Hungary: an economic geography, Westview Press, 1976, p. 23

- Miklós Molnár, A concise history of Hungary, Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 42 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Elena Mannová, Blanka Brezováková, A concise history of Slovakia, Historický ústav SAV, 2000, p. 88 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Joseph Slabey Rouček, Contemporary Europe: a study of national, international, economic, and cultural trends. A symposium, D. Van Nostrand Co., 1947, p. 424 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- M. L. Bush, Servitude in modern times, Wiley-Blackwell, 2000, p. 143 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Éva Molnár, Hungary: essential facts, figures & pictures, MTI Media Data Bank, 1995 نسخة محفوظة 19 يناير 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Lauren S. Bahr, Bernard Johnston (M.A.), Collier's encyclopedia: with bibliography and index, Volume 12, P.F. Collier, 1993, p. 381-383 نسخة محفوظة 18 يناير 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Zoltán Halász, Hungary: a guide with a difference, Corvina Press, 1978, pp. 20-22 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Joseph Held, Hunyadi: legend and reality, East European Monographs, 1985, p. 59 نسخة محفوظة 18 يناير 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- George Richard Potter, The New Cambridge modern history: The Renaissance, 1493-1520, CUP Archive, 1971, p. 405 نسخة محفوظة 25 فبراير 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- The New review, Volume 6, World Federation of Ukrainian Former Political Prisoners and Victims of the Soviet Regime, A. Pidhainy., 1966, p. 25 نسخة محفوظة 03 يونيو 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Leslie Konnyu, Hungarians in the United States: an immigration study, American Hungarian Review, 1967, p. 4 نسخة محفوظة 05 يونيو 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- László Kósa, István Soós, A companion to Hungarian studies, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1999, p. 16 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Teppo Korhonen, Helena Ruotsala, Eeva Uusitalo, Making and breaking of borders: ethnological interpretations, presentations, representations, Finnish Literature Society, 2003, p.39 نسخة محفوظة 03 يونيو 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Andrew L. Simon, Made in Hungary: Hungarian contributions to universal culture, Simon Publications LLC, 1998, p. 17 نسخة محفوظة 13 نوفمبر 2012 على موقع واي باك مشين. [وصلة مكسورة]

- Carlile Aylmer Macartney, The Habsburg Empire, 1790-1918, Macmillan, 1969, p. 79 نسخة محفوظة 04 يونيو 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- The spirit of Hungary: a panorama of Hungarian history and culture, Stephen Sisa, Vista Books, 1990, p. 103 نسخة محفوظة 05 يونيو 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Alan Masters, Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, Infobase Publishing, 2009, p. 258 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Domokos G. Kosáry, A history of Hungary, The Benjamin Franklin bibliophile society, 1941, p. 79 نسخة محفوظة 05 يونيو 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Michael Hochedlinger, Austria's wars of emergence: war, state and society in the Habsburg monarchy, 1683-1797, Pearson Education, 2003, p. 21 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Stephen Denis Kertesz, Diplomacy in a whirlpool: Hungary between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, Greenwood Press, 1974, p. 191 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- The Ottomans and the Balkans: a discussion of historiography By Fikret Adanır, Suraiya Faroqhi p.333 نسخة محفوظة 03 يونيو 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين. [وصلة مكسورة]

- István György Tóth, Gábor Ágoston, Millenniumi magyar történet: Magyarország története a honfoglalástól napjainkig, Osiris, 2001, p. 321 نسخة محفوظة 19 يناير 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Rhoads Murphey, Ottoman warfare, 1500-1700, Rutgers University Press, 1999, p. 174 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Klára Papp – János Barta Jr., Minorities research 6., Kisebbségkutatás (Minorities Studies and Reviews) نسخة محفوظة 18 أكتوبر 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Lonnie Johnson, Central Europe: enemies, neighbors, friends, Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 100 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Eric H. Boehm, Historical abstracts: Modern history abstracts, 1450-1914, Volume 49, Issues 1-2, American Bibliographical Center of ABC-Clio, 1998, p. 331 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Imre Wellmann, A magyar mezőgazdaság a XVIII. században, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1979, p. 13 نسخة محفوظة 19 يناير 2020 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Rudolf Andorka, Determinants of fertility in advanced societies, Taylor & Francis, 1978, p. 93 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Raphael Patai, The Jews of Hungary: history, culture, psychology, Wayne State University Press, 1996, p. 201 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- David I. Kertzer, Aging in the past: demography, society, and old age, University of California Press, 1995, p. 130 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- M. L. Bush, Rich noble, poor noble, Manchester University Press ND, 1988, p. 19 نسخة محفوظة 03 يونيو 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Peter F. Sugar, Péter Hanák, تيبور فرانك, A History of Hungary, Indiana University Press, 1994 pp. 11-143. نسخة محفوظة 06 مارس 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 14, Americana Corp., 1966, p. 509 نسخة محفوظة 03 يونيو 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Jonathan Dewald, Europe 1450 to 1789: encyclopedia of the early modern world, Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004, p. 230 نسخة محفوظة 03 يونيو 2013 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Arthur J. Sabin, Red Scare in Court: New York Versus the International Workers Order, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999, p. 4 نسخة محفوظة 12 يناير 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Thomas Spira, German-Hungarian relations and the Swabian problem: from Károlyi to Gömbös, 1919-1936, East European quarterly, 1977, p. 2 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries, A history of Eastern Europe: crisis and change, Taylor & Francis, 2007, page 259, ISBN 978-0-415-36627-4

- Paul Lendvai, The Hungarians: a thousand years of victory in defeat, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2003, p.286 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- A Concise History of Hungary, by Miklós Molnár page 179

- Richard C. Frucht, Eastern Europe: an introduction to the people, lands, and culture / edited by Richard Frucht, Volume 1, ABC-CLIO, 2005, p. 356 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- Carl Cavanagh Hodge, Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800-1914: A-K, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008, p. 306 نسخة محفوظة 03 أبريل 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين.