هرم نفر إر كارع كاكاي

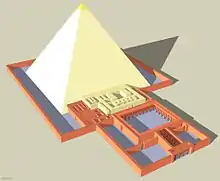

تميزت الأسرة الخامسة بنهاية الهياكل الهرمية العظيمة خلال عصر الدولة القديمة . كانت أهرامات هذا العصر أصغر وأصبحت أكثر توحيدًا على الرغم من انتشار زخرفة الإغاثة المعقدة. انحرف هرم نفر إر كارع كاكاي عن بقية الأهرام لأن تم بناؤه في الأصل كهرم مدرج : نشأ التصميم بعد الأسرة الثالثة (القرن 26 أو 27 ق.م.). [lower-alpha 2] تم بعد ذلك تنفيذ الهرم في الخطوة الثانية مع تعديلات تهدف إلى تحويله إلى هرم حقيقي ؛ [lower-alpha 3] ، ومع ذلك ترك وفاة الفرعون العمل ليتم الانتهاء من قبل خلفائه. تم الانتهاء من الأعمال المتبقية على عجل وذلك باستخدام مواد بناء أرخص.

| هرم نفر إر كارع كاكاي | |

|---|---|

| |

| إحداثيات | 29°53′42″N 31°12′09″E |

| الموقع | أبو صير، الجيزة |

| الدولة | |

| |

تم بناء هرم نفر إر كارع كاكاي [1] لفرعون الأسرة الخامسة نفر إر كارع كاكاي في القرن 25 ق.م. [2] [lower-alpha 1] كان أطول مبنى يقع على أعلى موقع في مقبرة أبو صير (البدرشين)وجدت بين الجيزة وسقارة وما زال بناء الهرم فوق المقبرة حتى اليوم. الهرم مهم أيضا لأن إخلائه أدى إلى اكتشاف برديات أبو صير .

بسبب الظروف افتقر نصب نفر إر كارع كاكاي إلى عدة عناصر أساسية لمجمع الهرم حيث لم يحتوى على معبد جنائزي أو جسر يصله بمعبد العبادة. بدلاً من ذلك تم استبدالهم بمستوطنة صغيرة من المنازل المبنية من الطوب اللبن جنوب الهرم حيث يمكن للكهنة العبادة وممارسة أنشطتهم اليومية، بدلاً من بلدة الهرم المعتادة بالقرب من معبد الوادي. واكتشاف برديات أبو صير في التسعينيات يرجع إلى هذا. عادة كان من الممكن احتواء البرديات في مدينة الهرم حيث كان من المؤكد تدميرها. أصبح الهرم جزءًا من مقبرة عائلية أكبر. يوجد بجوار الهرم بعض المعالم الأثرية مثل مقبرة الملكة خنتكاوس الثانية ؛ ويوجد مقابر أبناؤه نفر إف رع وني وسر رع في المناطق المحيطة. على الرغم من أن بنائها بدأ تحت حكام مختلفين فقد تم الانتهاء من هذه الآثار الأربعة جميعها في عهد ني وسر رع.

الموقع والحفر

يقع هرم نفر إر كارع كاكاي أعلى مقابر أبوصير بين سقارة وهضبة الجيزة . [14] افترض أن أبو صير كانت ذا أهمية كبيرة في الأسرة الخامسة بعد أن بنى أوسركاف ، أول حاكم معبده للشمس وقام خلفه ساحورع بافتتاح مقبرة ملكية هناك بنصب تذكاري جنائزي. [15] [16] كان خليفة ساحورع، [16] ابنه نفر إر كارع كاكاي هو الحاكم الثاني الذي يُدُفن في المقبرة. [15] [17] [18] [19] يقترح عالم المصريات جارومير كريجي عددًا من الفرضيات لموقف مجمع نفر إر كارع كاكاي فيما يتعلق بمجمع ساحور: (1) أن نفر إر كارع كاكاي كان مدفوعًا للنأي بنفسه عن ساحورع وبالتالي اختار العثور على مقبرة جديدة وإعادة تصميم خطة المقبرة لتمييزها عن ساحورع ؛ (2) أن الضغوط الجيومورفولوجية – خاصة المنحدر بين مجمعات نفر إر كارع كاكاي وساحورع – تطلبت من نفر إر كارع كاكاي تحديد موقع الدفن في مكان آخر ؛ (3) على أساس أن الموقع هو أعلى نقطة ربما اختارها نفر إر كارع كاكاي لضمان أن يهيمن مجمعه على المنطقة المحيطة ؛ (4) أنه قد تم اختيار الموقع عن قصد لبناء الهرم بما يتماشى مع مصر الجديدة . [20] [lower-alpha 4] يمثل خط أبوصير القطري خطًا تصوريًا يربط بين الزوايا الشمالية الغربية لأهرامات نفر إر كارع كاكاي وساحورع و نفر إف رع. وهو مشابه لمحور الجيزة الذي يربط الزوايا الجنوبية الشرقية لأهرامات الجيزة ويتقارب مع أبوصير إلى نقطة في مصر الجديدة. [27] [28]

أثر موقع المجمع على عملية البناء. يذكر عالم المصريات ميروسلاف بارتا أن أحد العوامل الرئيسية التي تؤثر على الموقع هو موقعهم بالنسبة إلى العاصمة الإدارية [lower-alpha 5] في المملكة القديمة [lower-alpha 6] المعروفة اليوم باسم ممفيس . [31] [32] بشرط أن يكون موقع ممفيس القديم معروفًا بدقة فإن مقبرة أب صير لم تتجاوز 4 كيلومتر (2.5 ميل) من وسط المدينة. [32] كانت الفائدة من قرب الموقع من المدينة هي زيادة الوصول إلى الموارد والقوى العاملة. [32] جنوب غرب أبوصير بحيث يمكن للعمال استغلال مقلع الحجر الجيري لجمع الموارد لتصنيع كتل البناء المستخدمة في بناء الهرم. كان المحجر الجيري هناك سهلاً بشكل خاص بالنظر إلى أن طبقات الحصى والرمل والتفلت تقع في الحجر الجيري إلى شرائح رفيعة تتراوح بين 0.60 متر (2.0 قدم) و 0.80 متر (2 قدم 7 بوصة) سميكة مما يجعلها أسهل لإزاحة من المصفوفة. [20]

في عام 1838 ، قام عالم المصريات البريطاني جون شاي بيرنج بإخلاء مداخل أهرامات ساحور ونفر إر كارع كاكاي ونيوسير . [33] وبعد خمس سنوات اكتشف عالم المصريات البروسي ريتشارد ليبسيوس مقبرة أبوصير ومخطط هرم نفر إر كارع كاكاي في القرن الحادي والعشرين . [33] كان ليبسيوس هو الذي اقترح النظرية التي تم فيها تطبيق طريقة طبقة التراكم [lower-alpha 7] للبناء على أهرامات الأسرة الخامسة والسادسة . [37] أحد التطورات المهمة اكتشاف برديات أبوصير ، التي عثر عليها في معبدنفر إف رع خلال الحفريات غير المشروعة في عام 1893. [33] في عام 1902عالم المصريات الألماني لودفيغ بورشاردت عمل في في البعثة الألمانية التي أنقذت تلك الأهرامات اكتشفت معابدها المجاورة والجسور المحفورة. [33] [15] تم نشر النتائج التي توصل إليها في 1909. [27] [38] كان لدى المعهد التشيكي لعلم المصريات مشروع تنقيب طويل الأجل يدور في الموقع منذ الستينيات. [15] [39]

مجمع الهرم

التخطيط

خضعت تقنيات بناء الأهرام لعملية انتقال في الأسرة الخامسة. [40] تضاءلت آثار الأهرامات ، وتضاءل تصميم معبد جنائزي تغيرت ، وأصبحت البنية التحتية للهرم موحدة. [40] [41] على النقيض من ذلك ، نقش بارز تكاثر الديكور [40] وتم إثراء المعابد بمجمعات تخزين أكبر. [41]

لقد تطور هذان التغييران المفاهيميان بحلول وقت حكم ساحورع على أبعد تقدير. يشير مجمع ساحورع الجنائزي إلى أن التعبير الرمزي من خلال الزخرفة أصبح مفضلاً على الحجم الهائل. على سبيل المثال ، احتوى مجمع الأسرة الرابعة للملك خوفو على إجمالي 100 متر طولي (330 قدمًا طوليًا) مخصصًا للزخرفة ، بينما كان معبد ساحورع يحتوي على حوالي 370 مترًا طوليًا (1200 قدمًا طوليًا) مخصصًا للإغاثة الزخارف. [42] يحدد Bárta أن مساحة التخزين في المعابد الجنائزية تتسع باستمرار منذ عهد هرم نفر إر كارع وما بعده. [43] كان هذا نتيجة لـ المركزة المشتركة للتركيز الإداري على العبادة الجنائزية ، وزيادة عدد الكهنة والمسؤولين المشاركين في الحفاظ على الطائفة ، وزيادة عائداتهم. [44] [45] اكتشاف بقايا كبيرة من الأواني الحجرية - معظمها مكسورة أو غير مكتملة - في المعابد الهرمية في ساحورع ، ونفيرركاري ، و نفر ف رع يشهد على هذا التطور. [46]

تتكون المجمعات الجنائزية في الدولة القديمة من خمسة مكونات أساسية: (1) معبد الوادي. (2) طريق. (3) معبد جنائزي. (4) هرم العبادة. و (5) الهرم الرئيسي. [47] كان لمجمع الجنائز في نفر إر كارع عنصرين فقط من هذه العناصر الأساسية: معبد جنائزي تم بناؤه على عجل من طوب اللبن والخشب الرخيص ؛ [48] [49] [50] وأكبر هرم رئيسي في الموقع. [51] تم اختيار معبد الوادي والجسر اللذين كانا مخصصين في الأصل لنصب نفر إر كارع التذكاري بواسطة ني اوسر رع لإنشاء مجمع الجنائز الخاص به. [52] على العكس من ذلك ، هرم العبادة لم يتم بناءه أبدًا ، كنتيجة لـ الاندفاع لإكمال النصب التذكاري بعد وفاة نفركيركير. [53] كان استبداله عبارة عن مستوطنة صغيرة ومساكن شيدت من الطوب اللبن إلى الجنوب من المجمع حيث يعيش الكهنة. [53] من الطوب الهائل تم بناء جدار الإغلاق حول محيط الهرم والمعبد الجنائزي لإكمال النصب الجنائزي لنفر إر كارع [53]

الهرم الرئيسي

كان المقصود من هذا البناء أن يكون هرمًا مدرجًا وهو اختيار غير عادي لملك الأسرة الخامسة بالنظر إلى أن عصر الأهرامات المدرجة قد انتهى مع عصر الأسرة الثالثة (القرن 26 أو القرن 27 قبل الميلاد) ، وهذا يتوقف على الباحث والمصدر. [54] [27] [55] [56] السبب وراء هذا الاختيار غير مفهوم. [14] [17] ينظر عالم المصريات ميروسلاف فيرنر إلى وجود علاقة تكهنية بأن نفر إر كارع كاكاي كان "مؤسس سلالة جديدة" [lower-alpha 8] على الرغم من أنه يفكر أيضًا في إمكانية وجود أسباب دينية و سياسة قوية كذلك. [17] احتوى المبنى الأول على ست خطوات وضعت بعناية [62] [lower-alpha 9] من الكتل الحجرية عالية الجودة [67] يصل ارتفاعها إلى 52 متر (171 قدم؛ 99 ذراع). [27] كان من المفترض تطبيق غلاف من الحجر الجيري الأبيض على الهيكل [67] ولكن بعد اكتمال الحد الأدنى من العمل على ذلك امتد فقط إلى المصصطبة الأولى [27] أعيد تصميم الهرم ليشكل "هرمًا حقيقيًا". [62] [27] يصف فيرنر هيكل هرم الأسرة الخامسة على هذا النحو ؛

بنية الهرم

شيدت سقوف الدفن والحجر الأمامي بثلاث طبقات من الحجر الجيري. تشتت الحزم الوزن من البنية الفوقية على جانبي المم مما يمنع الانهيار. [62] [17] نهب اللصوص غرف الحجر الجيري مما جعل من المستحيل إعادة بنائها بشكل صحيح [17] على الرغم من أنه لا يزال من الممكن تمييز بعض التفاصيل. وهي كانت كلتا الغرفتين موجهتين على طول المحور الشرقي الغربي وكان كلا المجلسين متماثلين كان غرفة الانتظار أقل من الاثنين و كلتا الغرفتين كان لها نفس سقف النمط ويحتويان على طبقة واحدة من الحجر الجيري. [17]

بشكل عام البنية التحتية تالفة بشكل كبير: غطى انهيار طبقة من عوارض الحجر الجيري غرفة الدفن. [62] لم يتم العثور على أي أثر للمومياء أو التابوت أو أي معدات للدفن في الداخل. [17] [62] شدة الأضرار التي لحقت البنية التحتية يمنع المزيد من الحفر. [14]

برديات أبو صير

.jpg.webp)

تأتي أهمية الهرم من ظروف بنائه ومحتوياته من المحفوظات من برديات أبو صير. [17] [62] [68] يقول عالم المصريات الفرنسي نيكولاس غريمال : "كانت أهم مجموعة معروفة من البرديات من المملكة القديمة حتى بعثة 1982 للمعهد المصري لجامعة براغ اكتشف حتى مخبأ أكثر ثراءً في مخزن لمعبد التحنيط القريب من نفر إف رع. " [68]

تم اكتشاف أول بقايا من ورق البردي من قبل الحفارين غير الشرعيين في عام 1893 [33] وبيعها وتوزيعها في جميع أنحاء العالم في سوق الآثار. [69] لاحقًا اكتشف بورشاردت بقايا إضافية أثناء التنقيب في نفس المنطقة. [70] وجدت بقايا مكتوبة بخط هرمي . كتبت المخطوطة بالهيروغليفية. [62] البرديات الأخرى الموجودة في قبر نفر إر كارع كاكاي تمت دراستها ونشرها بشكل كامل من قبل عالم المصريات الفرنسي بول بوسنر كريجر . [62] [70]

تمتد سجلات البرديات خلال الفترة الممتدة بين عهد جدكاري إيسي وحتى عهد بيبي الثاني. [68] وتسرد السجلات جميع جوانب إدارة العبادة الجنائزية للملك بما في ذلك الأنشطة اليومية للكهنة والرسائل. [33] [70] [71] المهم أن يربط البردي الصورة الأكبر للتفاعل بين المعبد الجنائزي ومعبد الشمس والمؤسسات الأخرى. [70] على سبيل المثال تشير الأدلة المجزأة على أوراق البردي إلى أن البضائع الخاصة بعبادة نفر إر كارع كاكاي الجنائزية قد تم نقلها بواسطة السفن إلى مجمع هرم الملك. [20] المدى الكامل لسجلات البرديات التي عثر عليها في أبو صير غير معروف لأن النتائج الأخيرة لا تزال غير منشورة. [33]

ملاحظات

- Proposed dates for Neferirkare Kakai's reign: c. 2492 – 2482 BC,[3][2] c. 2477–2467 BC,[4] c. 2475 – 2455 BC,[5] c. 2446 – 2438 BC,[6] c. 2446 – 2426 BC,[7] c. 2373 – 2363 BC.[8]

- Proposed dates for the Third Dynasty: c. 2700 – 2625 BC,[9] c. 2700 – 2600 BC,[10] c. 2687 – 2632 BC,[3] c. 2686 – 2613 BC,[5] c. 2680 – 2640 BC,[11] c. 2650 – 2575 BC,[7] c. 2649 – 2575 BC,[6] c. 2584 – 2520[12]

- The term "true pyramid" refers to pyramids which have the هرم. That is, they have a square base with four triangular faces converging to a single point at the apex.[13]

- Heliopolis, or Iunu, was a major city of ancient Egypt.[21] The temple of Heliopolis housed the sacred stone of بن بن[22] – the primeval hill which arose from the primordial waters of Nu.[23] The temple was also the location of the cult of the sun god,[24] Atum.[25] The Egyptologist Mark Lehner proposes that the pyramids relation to the temple of Heliopolis is evidence in support of the pyramid being a sun symbol.[26]

- Administrative centres in the early Old Kingdom period generally consisted of officials, personnel and some craftsmen. Memphis was the largest of these centres, and housed the royal court of the pharaoh during the Old Kingdom. The exact extent of the spatial organization of Memphis in the Old Kingdom remains unknown, though it was most probably not densely populated or walled like its contemporaries such as Sumerian cities. Most of the population of Egypt lived as peasant farmers in rural communities.[29]

- transl. inbw-ḥḏ[30]

- A solid central limestone core is constructed[34] and encased in successive layers of small stone blocks laid at an inwards slant.[34][35] As a result of the inwards tilt of each layer, the pyramid had a slope of about 74°.[34] These blocks were roughly dressed with the exception of the outer edge of each layer which was smoothed to flatten the surface.[35] This was the method of construction applied to Third Dynasty step pyramids.[34][35][36]

- The division of the Turin Canon into dynasties is a contested topic. The Egyptologist Jaromír Málek holds the conviction that the divisions in kinglists coincide with the transfer of the royal residence and believes that the introduction of dynasties, as used in modern study, began with مانيتون.[57] Similarly, the Egyptologist Stephan Seidlmayer, considers the break in the Turin Canon at the end of the Eighth Dynasty to represent the relocation of the royal residence from Memphis to Herakleopolis.[58] The Egyptologist John Baines does not accept Malek's explanation for these features, and instead believes that the list is divided into dynasties with totals given at the end of each, though only few such divisions have survived.[59] Similarly, Professor John Van Seters views the breaks in the canon as divisions between dynasties, but in contrast, states that the criterion for these divisions remains unknown. He speculates that the pattern of dynasties may have been taken from the nine divine kings of the التاسوع المقدس.[60] The Egyptologist يان شو believes that the Turin Canon gives some credibility to Manetho's division of dynasties, but considers the king lists to be a form of ancestor worship and not a historical record.[61]

- It was originally believed that the pyramid was built by layering small rectangular stone blocks – which measured up to two feet (six-tenths of a metre) in length – and were angled inwards towards a solid core.[63] This theory was proposed initially by Richard Lepsius, a German Egyptologist who visited the site briefly in the 1830s, and propagated by the archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt, who conducted excavations in Egypt, including at Neferirkare's pyramid, at the start of 20th century, after discovering what he believed were accretion layers on "internal faces" of the pyramids at Abusir.[63][64] It was challenged by Vito Maragioglio and Celeste Rinaldi who conducted careful examinations of pyramidal architecture in the Old Kingdom and failed to find blocks lying on a slant in any Fourth or Fifth Dynasty pyramid they studied. Rather, they found that in each instance these blocks were always set horizontally. This lead them to reject the accretion layer hypothesis.[63] The theory was effectively disproven by the Czech excavation team at Abusir led by Egyptologist Miroslav Verner.[63][64] The unfinished nature of Neferefre's monument allowed Verner's team to test Lepsius and Borchardt's hypothesis; if the pyramid had been constructed as suggested, then underneath the clay and desert stone capping, the pyramid's structure would have resembled the layers of an onion.[65] Instead the excavators found that the pyramid of Neferefre and pyramid of Neferirkare consisted of: an outer retaining wall of four or five courses of large horizontally layered stone blocks;[65] an inner pit of small horizontally layered roughly dressed limestone blocks;[66] with the gap between the two frames filled with a mash of crude limestone chunks, mortar and sand;[65][66] and not in the slanted fashion proposed by the accretion layer theory.[63][64][65]

المراجع

- Arnold 2003، صفحة 160.

- Verner 2001c، صفحة 589.

- Altenmüller 2001، صفحة 598.

- Clayton 1994، صفحة 30.

- Shaw 2003، صفحة 482.

- Allen et al. 1999، صفحة xx.

- Lehner 2008، صفحة 8.

- Dodson & Hilton 2004، صفحة 288.

- Grimal 1992، صفحة 389.

- Arnold 2003، صفحة 265.

- Verner 2001e، صفحة 473.

- Dodson & Hilton 2004، صفحة 287.

- Verner 2001d، صفحات 87 & 89.

- Arnold 2003.

- Verner 2001b.

- Bárta 2017.

- Verner 2001e.

- Dodson 2016.

- Bárta 2015.

- Krejčí 2000.

- Allen 2001، صفحة 88.

- Lehner 2008، صفحة 32.

- Verner 1994، صفحة 135.

- Verner 2001e، صفحة 34.

- Myśliwiec 2001، صفحة 158.

- Lehner 2008، صفحة 34.

- Verner 1994.

- Isler 2001.

- Bard 2015، صفحة 138.

- Jefferys 2001، صفحة 373.

- Jefferys 2001.

- Bárta 2005.

- Edwards 1999.

- Lehner 1999، صفحة 778.

- Sampsell 2000، Vol 11, No. 3 the Ostracon.

- Isler 2001، صفحة 96.

- Sampsell 2000.

- Borchardt 1909.

- Krejčí 2015.

- Verner 2001d، صفحة 90.

- Bárta 2005، صفحة 185.

- Bárta 2005، صفحات 183–185.

- Bárta 2005، صفحة 186.

- Bárta 2005، صفحات 185 –188.

- Loprieno 1999، صفحة 41.

- Allen et al. 1999، صفحة 125.

- Bárta 2005، صفحة 178.

- Verner 2001e، صفحة 293.

- Lehner 2008، صفحة 144.

- Verner 1994، صفحات 77–79.

- Verner 2001e، صفحة 291.

- Lehner 2008، صفحة 148.

- Verner 2001e، صفحة 296.

- Altenmüller 2001.

- Verner 2002.

- Kahl 2001.

- Malek 2003، صفحة 84 & 103 – 104.

- Seidlmayer 2003، صفحة 108.

- Baines 2007، صفحة 198.

- Seters 1997، صفحات 135 – 136.

- Shaw 2003، صفحات 7 – 8.

- Lehner 2008.

- Sampsell 2000، Vol 11, No. 3 The Ostracon.

- Verner 2002، صفحات 50 – 52.

- Lehner 2008، صفحة 147.

- Verner 2014، Neferefre's (unfinished) pyramid.

- Verner 2014.

- Grimal 1992.

- Davies & Friedman 1998.

- Strudwick 2005.

- Allen et al. 1999.

مصادر

- Allen, James; Allen, Susan; Anderson, Julie; et al. (1999). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-8109-6543-0. OCLC 41431623. مؤرشف من الأصل في 30 نوفمبر 2020. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Allen, James P. (2001). "Heliopolis". In Redford (المحرر). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. صفحات 88–89. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Altenmüller, Hartwig (2001). "Old Kingdom: Fifth Dynasty". In Redford (المحرر). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. صفحات 597–601. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Altenmüller, Hartwig (2002). "Funerary Boats and Boat Pits of the Old Kingdom". In Coppens, Filip (المحرر). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2001 (PDF). 70. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. صفحات 269–290. ISSN 0044-8699. مؤرشف من الأصل (PDF) في 31 أكتوبر 2020. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Arnold, Dieter (2003). The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture. London: I.B Tauris & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-1-86064-465-8. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Baines, John (2007). Visual and Written Culture in Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815250-7. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Bard, Kathryn (2015). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Chicester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-89611-2. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Bareš, Ladislav (2000). "The destruction of the monuments at the necropolis of Abusir". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (المحررون). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. صفحات 1–16. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Bárta, Miroslav (2005). "Location of the Old Kingdom Pyramids in Egypt". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. Cambridge. 15 (2): 177. doi:10.1017/s0959774305000090. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Bárta, Miroslav (2015). "Abusir in the Third Millennium BC". CEGU FF. Český egyptologický ústav. مؤرشف من الأصل في 27 أكتوبر 2020. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 01 فبراير 2018. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Bárta, Miroslav (2017). "Radjedef to the Eighth Dynasty". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. مؤرشف من الأصل في 30 يناير 2021. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Borchardt, Ludwig (1909). Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Nefer-Ir-Ke-Re. (باللغة الألمانية). Leipzig: Hinrichs. doi:10.11588/diglit.30508. مؤرشف من الأصل في 11 فبراير 2020. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Davies, William V.; Friedman, Renée F. (1998). Egypt Uncovered. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang. ISBN 978-1-55670-818-3. مؤرشف من الأصل في 17 أكتوبر 2020. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Dodson, Aidan (2016). The Royal Tombs of Ancient Egypt. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-2159-0. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05128-3. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Dušek, Jan; Mynářová, Jana (2012). "Phoenician and Aramaic Inscriptions from Abusir". In Botta, Alejandro (المحرر). In the Shadow of Bezalel. Aramaic, Biblical, and Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of Bezalel Porten. 60. Leiden: Brill. صفحات 53–69. ISBN 978-90-04-24083-4. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Edwards, Iorwerth (1975). The pyramids of Egypt. Baltimore: Harmondsworth. ISBN 978-0-14-020168-0. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Edwards, Iorwerth (1999). "Abusir". In Bard (المحرر). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. صفحات 97–99. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Goelet, Ogden (1999). "Abu Ghurab/Abusir after the 5th Dynasty". In Bard (المحرر). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. صفحة 87. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Isler, Martin (2001). Sticks, Stones, and Shadows: Building the Egyptian Pyramids. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3342-3. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Jefferys, David (2001). "Memphis". In Redford (المحرر). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. صفحات 373–376. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Kahl, Jochem (2001). "Old Kingdom: Third Dynasty". In Redford (المحرر). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. صفحات 591–593. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Krejčí, Jaromír (2000). "The origins and development of the royal necropolis at Abusir in the Old Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (المحررون). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. صفحات 467–484. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Krejčí, Jaromír (2015). "Abúsír". CEGU FF (باللغة التشيكية). Český egyptologický ústav. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 21 يناير 2018. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Lehner, Mark (1999). "pyramids (Old Kingdom), construction of". In Bard (المحرر). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. صفحات 778–786. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Loprieno, Antonio (1999). "Old Kingdom, overview". In Bard (المحرر). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. صفحات 38–44. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Malek, Jaromir (2000). "Old Kingdom rulers as "local saints" in the Memphite area during the Old Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (المحررون). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. صفحات 241–258. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Malek, Jaromir (2003). "The Old Kingdom (c. 2686 – 2160 BC)". In Shaw (المحرر). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. صفحات 83–107. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Morales, Antonio J. (2006). "Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír (المحررون). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005, Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague (June 27–July 5, 2005). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. صفحات 311–341. ISBN 978-80-7308-116-4. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Myśliwiec, Karol (2001). "Atum". In Redford (المحرر). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. صفحات 158−160. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Sampsell, Bonnie (2000). "Pyramid Design and Construction – Part I: The Accretion Theory". The Ostracon. Denver. 11 (3). مؤرشف من الأصل في 26 يناير 2021. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Seidlmayer, Stephen (2003). "The First Intermediate Period (c. 2160 – 2055 BC)". In Shaw (المحرر). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. صفحات 108–136. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Seters, John Van (1997). In Search of History: Historiography in the Ancient World and the Origins of Biblical History. Warsaw, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-013-2. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Shaw, المحرر (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Strudwick, Nigel (2005). Leprohon, Ronald (المحرر). Texts from the Pyramid Age. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-13048-7. مؤرشف من الأصل في 16 يناير 2018. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Verner, Miroslav (1994). Forgotten pharaohs, lost pyramids: Abusir (PDF). Prague: Academia Škodaexport. ISBN 978-80-200-0022-4. مؤرشف من الأصل (PDF) في 01 فبراير 2011. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Verner, Miroslav (2001a). "Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology" (PDF). Archiv Orientální. Prague. 69 (3): 363–418. ISSN 0044-8699. مؤرشف من الأصل (PDF) في 04 فبراير 2021. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Verner, Miroslav (2001b). "Abusir". In Redford (المحرر). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. صفحات 5–7. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Verner, Miroslav (2001c). "Old Kingdom". In Redford (المحرر). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. صفحات 585–591. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Verner, Miroslav (2001d). "Pyramid". In Redford (المحرر). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. صفحات 87–95. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Verner, Miroslav (2001e). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1703-8. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Verner, Miroslav (2002). Abusir: Realm of Osiris. Cairo; New York: American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-424-723-1. مؤرشف من الأصل في 07 ديسمبر 2018. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Verner, Miroslav (2014). The Pyramids. New York: Atlantic Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78239-680-2. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

صور وملفات صوتية من كومنز

صور وملفات صوتية من كومنز

- بوابة مصر

- بوابة علم الآثار

- بوابة مصر القديمة