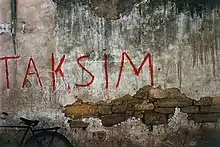

تقسيم (نزاع قبرص)

التقسيم (بالتركية: Taksim) كان هدف القبارصة الأتراك الذين دعموا تقسيم جزيرة قبرص إلى أجزاء تركية ويونانية، وهو مفهوم أعلن عنه في وقت مبكر من عام 1957 من قبل الدكتور فاضل كوجوك.[1]

تطورت القومية التركية في قبرص بشكل أساسي استجابةً للقومية اليونانية والرغبة في اتحاد الجزيرة بأكملها مع اليونان.[2][3][4] في البداية، فضل القبارصة الأتراك استمرار الحكم البريطاني.[5] ومع ذلك، فقد انزعجوا من دعوات القبارصة اليونانيين إلى التوحيد مع اليونان، لأنهم رأوا أن اتحاد جزيرة كريت مع اليونان قد أدى إلى هجرة الأتراك الكريتيين، وهي سابقة يجب تجنبها، [6][7] واتخذوا الموقف المؤيد للتقسيم رداً على النشاط العسكري للمنظمة الوطنية للمقاتلين القبارصة.[8] كما يعتبر القبارصة الأتراك أنفسهم مجموعة عرقية مميزة للجزيرة ويعتقدون أن لهم حقًا منفصلاً في تقرير المصير عن القبارصة اليونانيين.[9] في غضون ذلك، في الخمسينيات من القرن الماضي، اعتبر الزعيم التركي عدنان مندريس قبرص "امتدادًا للأناضول"، ورفض تقسيم قبرص على أسس عرقية وأيد ضم الجزيرة بأكملها إلى تركيا. وركزت الشعارات القومية على فكرة أن "قبرص تركية"، وأعلن الحزب الحاكم أن قبرص جزء من الوطن التركي وحيوية لأمنها. عند إدراك أن القبارصة الأتراك كانوا 20٪ فقط من سكان الجزر، وبالتالي كان الضم غير ممكن، تم تغيير السياسة الوطنية لصالح التقسيم. كثيرا ما استخدم شعار "التقسيم أو الموت" في احتجاجات القبارصة الأتراك والأتراك في أواخر الخمسينيات وطوال الستينيات. على الرغم من أنه بعد مؤتمري زيورخ ولندن، بدت تركيا وكأنها تقبل بوجود الدولة القبرصية وتنأى بنفسها عن سياستها في تفضيل تقسيم الجزيرة، إلا أن هدف زعماء القبارصة الأتراك والأتراك ظل هو إنشاء دولة تركية مستقلة في الجزء الشمالي من الجزيرة.[10][11]

انظر أيضًا

المراجع

- "Internet Archive Wayback Machine". Web.archive.org. 2006-06-15. مؤرشف من الأصل في 15 يونيو 2006. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 25 يناير 2012. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Kyris, George (2016). The Europeanisation of Contested Statehood: The EU in Northern Cyprus. Routledge. صفحات 30–1. ISBN 1317032748. مؤرشف من الأصل في 13 أغسطس 2020.

The rise of Turkish nationalism among the Turkish Cypriots can be largely seen as a response to the Greek Cypriot national "awakening" and campaign for union with Greece.

الوسيط|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Kızılyürek, Niyazi (2003). "The politics of identity in the Turkish Cypriot community : a response to the politics of denial?". Travaux de la Maison de l'Orient méditerranéen. 37 (1): 197–204. مؤرشف من الأصل في 30 مارس 2019.

The Turkish Cypriot nationalism developed mainly in reaction to the Greek Cypriot national desire for union with Greece.

الوسيط|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Carter, Judy; Irani, Irani; Volkan, Vamık (2015). Regional and Ethnic Conflicts: Perspectives from the Front Lines. Routledge. صفحة 60. ISBN 1317344669. مؤرشف من الأصل في 13 أغسطس 2020. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Papadakis, Yiannis; Peristianis, Nicos; Welz, Gisela (July 18, 2006). Divided Cyprus: Modernity, History, and an Island in Conflict. Indiana University Press. صفحة 2. ISBN 9780253111913. مؤرشف من الأصل في 13 أغسطس 2020. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Isachenko, Daria (2012). The Making of Informal States: Statebuilding in Northern Cyprus and Transdniestria. Palgrave Macmillan. صفحة 37. ISBN 9780230392076. مؤرشف من الأصل في 13 أغسطس 2020. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Pericleous, Chrysostomos (2009). Cyprus Referendum: A Divided Island and the Challenge of the Annan Plan. I.B.Tauris. صفحات 135–6. ISBN 9780857711939. مؤرشف من الأصل في 13 أغسطس 2020. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Mirbagheri, Farid (2009). Historical Dictionary of Cyprus. Scarecrow Press. صفحة xiv. ISBN 9780810862982.

Greek Cypriots engaged in a military campaign for enosis, union with Greece. Turkish Cypriots, in response, expressed their desire for taksim, partition of the island.

الوسيط|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Diez, Thomas (2002). The European Union and the Cyprus Conflict: Modern Conflict, Postmodern Union. Manchester University Press. صفحة 83. ISBN 9780719060793. مؤرشف من الأصل في 13 أغسطس 2020. الوسيط

|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - Behlul (Behlul) Ozkan (Ozkan) (26 June 2012). From the Abode of Islam to the Turkish Vatan: The Making of a National Homeland in Turkey. Yale University Press. صفحة 199. ISBN 978-0-300-18351-1. مؤرشف من الأصل في 29 يوليو 2020.

In line with the nationalist rhetoric that "Cyprus is Turkish", Menderes predicated his declaration upon the geographic proximity between Cyprus and Anatolia, thereby defining "Cyprus as an extension of Anatolia". It was striking that Menderes rejected partitioning the island into two ethnic states, a position that would define Turkey's foreign policy regarding Cyprus after 1957

الوسيط|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة) - G. Bellingeri; T. Kappler (2005). Cipro oggi. Casa editrice il Ponte. صفحة 27. ISBN 978-88-89465-07-3. مؤرشف من الأصل في 13 أغسطس 2020.

The educational and political mobilisation between 1948-1958, aiming at raising Turkish national consciousness, resulted in the involving Turkey as motherland in the Cyprus Question. From then on, Turkey, would work hand in hand with the Turkish Cypriot leadership and the British government to oppose the Greek Cypriot demand for Enosis and realise the partition of Cyprus, which meanwhile became the national policy.

الوسيط|CitationClass=تم تجاهله (مساعدة)

- بوابة قبرص

- بوابة السياسة

- بوابة تركيا